Cold Case Homicide

A Western Australia Perspective

- Category: Homicide

- Tags: Free To Read, investigations, Murder, Western Australia, WAPOL, Forensics, Perth, Media, Cold case homicide, Quentin Flatman, Allyson Beaton, Sally Coombes

HISTORICAL HOMICIDE INVESTIGATIONS

This article seeks to explore the difficulties and challenges with investigating cold case homicides within Western Australia. This article does not offer complex solutions. Instead, given the limited context, challenges are identified and briefly discussed.

Cold case homicide investigation is unique because, while a contemporary investigation, it works upon dated practices and evidence. In some instances, the quality of investigations is such that it seeks to correct the errors of the past with the benefit of hindsight.

Comparatively, this investigative specialisation has the smallest victim pool within the Western Australia Police Force (the Agency) yet has the potential to cause significant reputational harm.

Within the cold case sphere, even when investigators get it right; they get it wrong.

The authors submit that an increased community expectation to resolve unsolved cold case homicides has arisen since the arrest and conviction of Claremont serial killer, Bradley Edwards (below).

In essence, the WA Police Special Crime Squad – Homicide has become a victim of its own success, which presents a challenge in community confidence for police to investigate and arrest offenders. These matters tend to become part of community folklore and reflect on the performance of a policing agency.

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION

When considering the conduct and actions of previous investigations, great care is taken to not criticise the investigative processes employed by officers at the time and attribute blame because “the detectives should have known better”. Making those assessments with the benefit of hindsight adds no value and can be counterproductive.

DNA technology could not be foreseen by investigators of crimes that occurred before its development. This, together with improved investigative practices and case management, makes it difficult to lay blame based on our predecessors performing poorly. Similarly, current criminal investigators do not know what new technology, investigative strategies or case management will become relevant in criminal investigations in the future. Tools that we use today may seem farcical to investigators in the future.

Regardless, today’s forensic advancements will not stop the media or the courts adversely criticising the historical actions of police, leading to an erosion of public confidence.

A former Police Commissioner addressed these issues whilst discussing a 40-year-old high profile matter in Western Australia, when he wrote:

‘There is no doubt that recent disclosures in the (name deleted) case do require thorough investigation but the use of the word ‘are’ instead of ‘were’, is of course, absurd when applied to a matter 40 years’ old. The Police Force of 1975 was a place of much less accountability and a limited capacity to implement the levels of accountability we have today. There were no computers, no electronic recording systems, no automatic vehicle location and no DNA to provide a few examples. In such an environment, it is reasonable to look back and question the way business was done and to raise concerns about the police. Reports in this paper quite rightly point out that there have been rumours besetting this inquiry for the past 40 years and there have been reviews that have led nowhere.

But rumours are not evidence and they get retold and embellished. The truth invariably depreciates with every retelling’.

INVESTIGATION

In commencing an investigation, the conduct of past and present meetings is invaluable in achieving a ‘real feel’ for the investigation and is a process that assists in all aspects of the cold case investigation.

Past and present meetings occur where former criminal and crime scene investigators are invited to discuss the conduct of the original inquiry, focusing discussions upon fact finding, the thoughts and feelings of the investigator, identifying matters that may not have been recorded and seeking rationale behind why a particular investigative strategy manifested or did not manifest.

In rare instances these meetings have revealed case file notes and other physical material which was found to be held by these officers. Notwithstanding previous comments relating to criticism of officers who investigated historical cases, current investigators should be conscious of their actions today, as we will all likely be requested to provide an insight to a matter investigated in the years to come.

With dozens of files held by the Special Crime Squad – Homicide, personal interest may bias which files are selected for investigation. Resources limit the number of files that can be investigated. Consequently, a “science” in case file selection is important to ensure the best utilisation of resources.

In commencing a cold case investigation, consideration is given to the factors that influence which files investigators choose to open. Often those of high community interest receive a greater amount of attention, while other files or investigations go largely forgotten despite the presence of investigative avenues. To counter this, the squad utilises an admiralty scale: The higher the rating within the scale, the greater the opportunity to resolve the crime through arrest, thus removing the potential for bias to influence decision making.

Within the agency’s cold case archive the original case files range from a single, lever-arch folder containing very few documents to numerous boxes overwhelming investigators with documentary data. Factors influencing this include age and the length of elapsed time before a person is reported missing (where they have disappeared in suspicious circumstances and hence typically contain the least amount of data). Others, which received significant media interest at the time, hold vast amounts of investigative material. A constant in all files is the continual improvement of investigations and information recording over time, superseding the single, lever-arch folder with greater amounts of data retained.

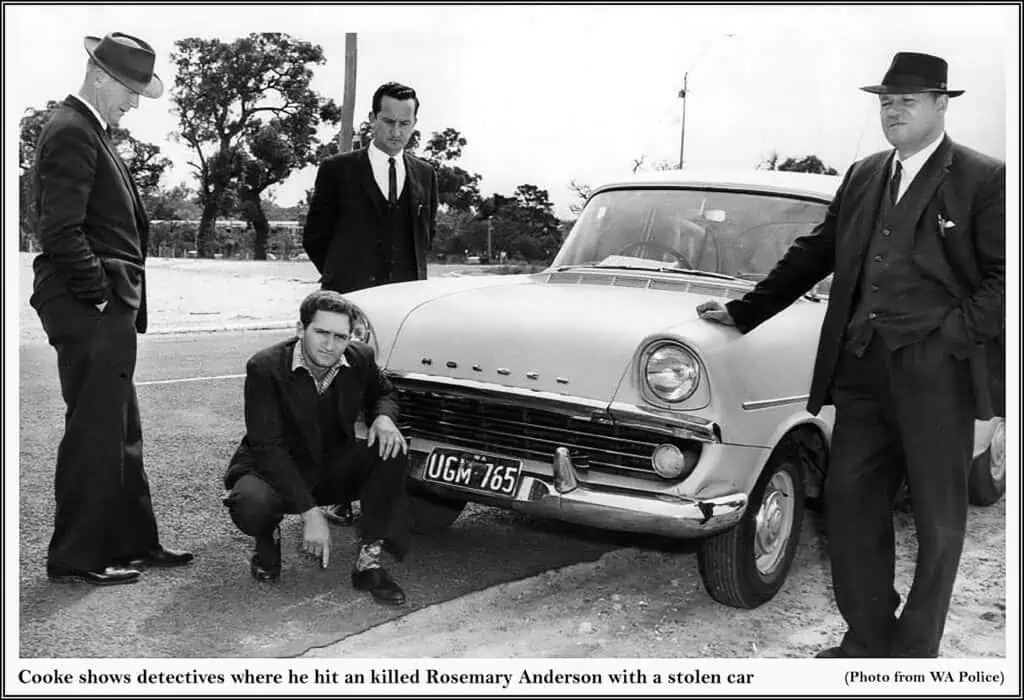

Above: Serial killer Eric Cooke confessing to Rose Anderson's murder, 1963 (image: WA Police Historical Society archives).

However, community interest in particular matters often becomes the motivation for files becoming subject to investigation. Improved forensic techniques and media interest can also drive the re-investigation of an offence. This was endorsed during an earlier study which found the impetus to open files was directly proportional to an account of physical evidence, the development of new DNA technologies, and media exposure. In this study, the least-recorded reasons for commencing a review were on account of prior convictions being overturned, recovered memory (discussed later), and information provided by a known witness.

This process, whilst based within a sound clinical selection criterion, does not consider the power and influence secondary victims hold within this crime type. Understandably, the need for closure and a constant search for answers and justice for a loved one is a powerful motivator for secondary victims; frustration in receiving a response — or lack of contact from police — can drive these victims to contact the media.

MEDIA: A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

The media plays a significant role in raising the expectations of solving cold case matters. This is supported by the community’s thirst for crime television dramas and a belief that television forensic technology applies to solving matters in the real world. Some journalists, lacking a complete knowledge of science themselves, seize upon this popularity, and report on matters in a manner which can create a false hope for secondary victims.

This combination can raise false hope for grieving family members. It can damage their confidence in police to investigate matters which, if expressed publicly, can tarnish the reputation of policing agencies and potentially impact judicial processes. Maintaining constructive relationships with family members can in part mitigate these issues, but their right to express their views, and the media’s right to report on these matters, must be honoured. With this media reporting, podcasts are quickly rising as the preferred media practice for such high profile and community interest matters.

Media reporting on unsolved matters remains a valuable investigative strategy in the progression of any police investigation. Partnerships with media agencies and the use of carefully planned media strategies are used by Law Enforcement Agencies (LEA) across the globe. However, unexpected, or unplanned attention on cold case matters can generate new information which must be carefully managed and responded to.

Sudden media attention on matters not currently subject to an active investigation can impact on active matters, causing diversion and catch-up, depleting investigative resources to respond to (and analyse) investigative actions generated. This can pose a challenge if consideration is given to the workload already being managed by cold case teams.

FORENSICS

While the seasoned investigator is aware of the ‘CSI factor’, in historical matters several complexities exist which require an ‘as is’ acceptance. As the cold case title suggests, the older the incident, the less likely exhibits have been collected, packaged and preserved at the standards we now apply.

Depending on the type of exhibit, deterioration occurs over time causing the item to be less valuable or able to provide results, should it be re-analysed.

Deterioration could include or be caused by:

- corrosion of the item;

- a weakening of DNA contained within blood samples due to age and exposure to heat; and

- storage vessels causing sweating, triggering mould and breaking down biological evidence or disrupting any visual or pattern evidence.

Storage practices employed at the time of seizure contribute to this deterioration. While some items were left stored ‘in the office’, such as under desks or in cupboards, those that made it to approved storage locations were typically housed in sheds or storerooms that were not climatically temperature controlled. Consequently, exhibits were exposed to extreme variances in temperature after being stored in buildings with no climate control, let alone being exposed to common vermin.

Further, items collected ‘back in the day’ were, on occasions, packaged together; increasing the possibility of cross contamination. Items that found their way to dedicated storage areas were sometimes subject to flooding, which consequently damaged and/ or destroyed exhibits and case files.

On commencing a forensic review, a scoping process is undertaken to identify the existence, location and availability of a case file. This process includes engagement with internal and partner agencies establishing what has been examined and its current status or location. The practice of ‘past and present’ meetings significantly assists in this process, as the forensic investigator can not only determine whether an exhibit exists or has been destroyed, but possibly identify items available for fresh analysis.

The way a person is killed can assist significantly in the investigation of cold case homicides. For example, a victim being subjected to a sustained assault may provide a greater chance of forensic evidence being tested. An example of this is the number of exhibits collected during the initial examination, with the number collected limited to the technology of the day.

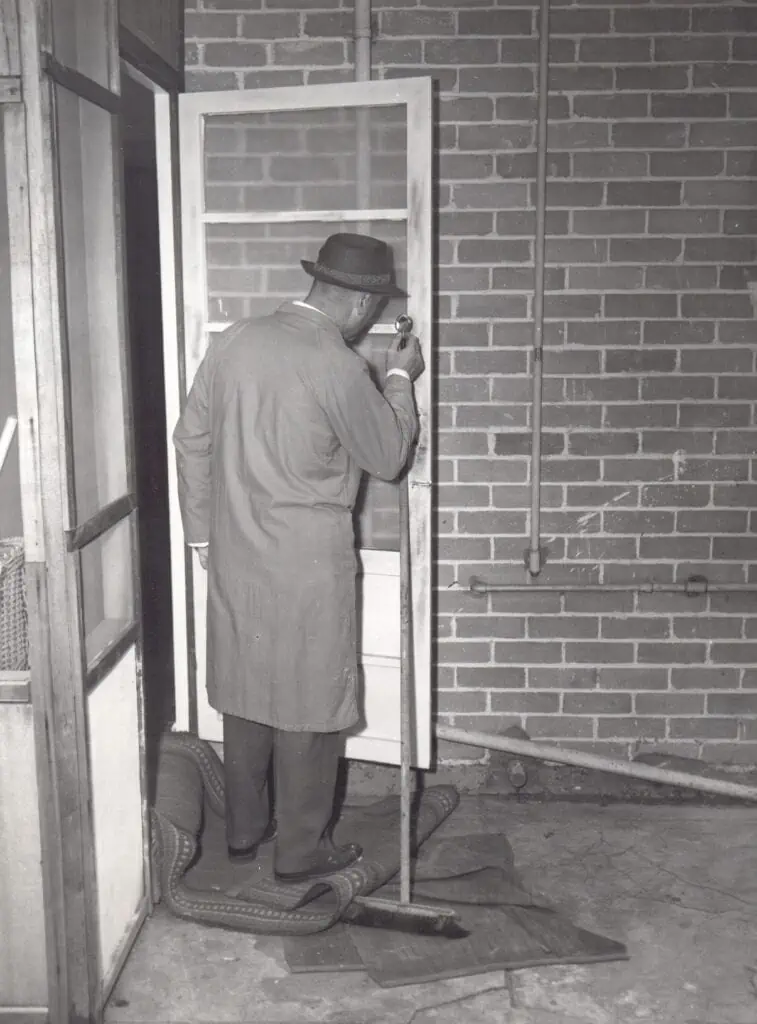

Unaware of future advancements in DNA forensic technology, previous collection techniques lacked the measures of utilising personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect an exhibit from contamination. It can be seen in videos and photographs of historical crime scenes that gloves, masks and protective overalls were not a consideration with officers even smoking cigarettes in situ at crime scenes and during the collection of evidence. It was also evident through photographs and video footage that any number of curious police officers would enter the crime scene simply to ‘have a look’ and not contribute to the investigative process.

As technology has evolved, forensic case file management systems have advanced, and interrogating these systems has proven to be troublesome. Numerous systems have evolved over the history of policing. In the case of paper-based systems, complications arise when attempting to locate all paperwork and other documentation. In the case of computerised systems, these older systems are problematic with current investigators lacking access to (or the knowledge to extract) the information required. Maintaining these old systems is also challenging as new systems may not be interoperable with transferring and extracting all relevant data.

Another challenge faced by forensic officers is the identification of ‘old’ offenders. There are cases where unknown DNA profiles are recorded on the National DNA Database because of recent re-examination of exhibits due to technological advances. These profiles remain unidentified as offenders who were actively offending apparently ceased doing so because of several factors, including developed social bonds (family or new acquaintances), a cognitive development (self-worth established through employment, or age) and not had their DNA taken prior to or since the introduction of legislation requiring a sample of DNA.

Advances in DNA technology increase the possibility of identification through familial searching. Because of a high-profile matter investigated by the agency, the WA Police Force has been extremely progressive in the collection of ‘identifying particulars’ from all arrested persons. This does not remain the panacea for historical investigations, however, because of the limited number of people recorded on the DNA database. As a nation, only 2% of the entire population is recorded within the National DNA database, with Western Australia holding 25% of that stake. With a national population of more than 25 million, only 500,000 persons are recorded. Nevertheless, this capability has enabled familial searching, resulting in several arrests for unsolved historical sexual offences.

There are several examples of long-term investigations which singularly focused on the resolution of a homicide through the identification of an offender through DNA and, by doing so, other investigative opportunities were missed. In considering the total population recorded on the DNA database, resolving a homicide through DNA remains a long shot. This is supported by the number of unidentified deceased persons held in mortuaries across the country.

Technological advances in various forensic fields mean that assistance can be sought across the globe. To ensure the continued relationship with local partners, who remain the primary partners of the agency, consideration of seeking results elsewhere always occurs with consultation, agreement and endorsement by these critical partners.

Care must be taken when using these external bodies, particularly when dealing with an ‘only for profit’ business specialising in this field. Identifying and verifying the credentials of these experts is important. This consideration is accompanied by weighing up the cost of testing and subsequent court appearances, which can be quite high.

Packaging and shipping of critical exhibits across the globe is done so at extreme risk should those items be lost. Despite these considerations, in some instances the results are both a joy and heartache.

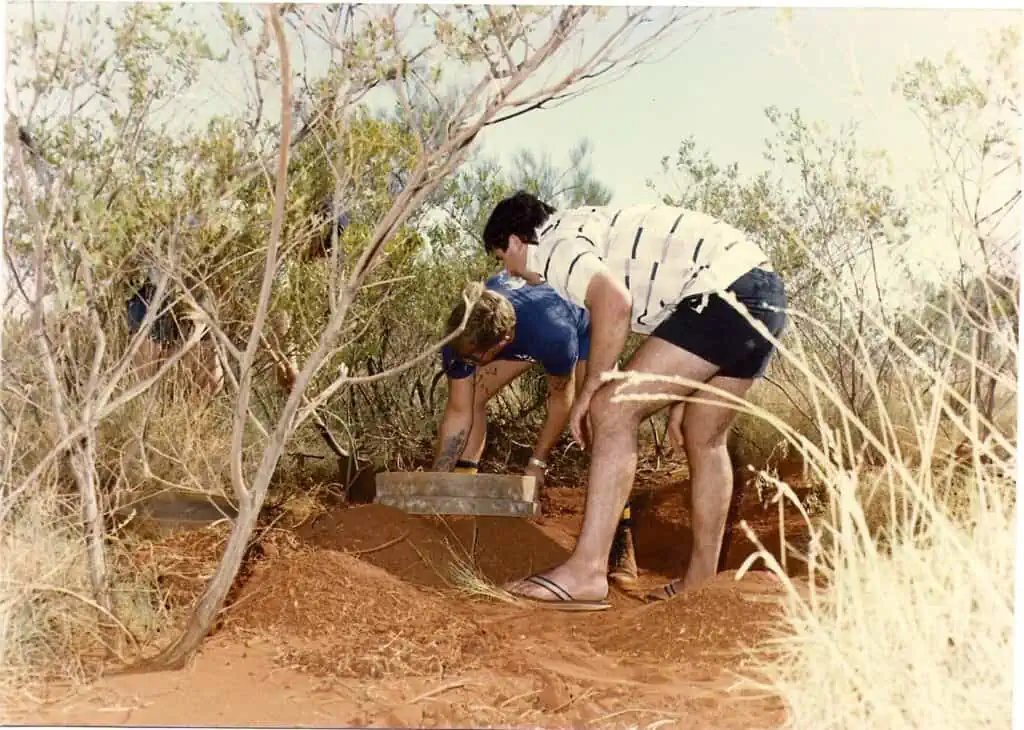

In the matter of an unsolved homicide in 1989, after consultation with PathWest (the local service provider) several exhibits were sent to an overseas company for examination.

During the life of the investigation, a single suspect had always been of interest to the squad, and it was hoped that this person’s DNA would be found on the deceased. After a significant amount of money had been invested in the search for DNA traces, the suspect was linked to the deceased.

However, the presence of the DNA was of such a minute quantity, its presence was explained because of the victim and suspect merely ‘brushing or shaking hands’ with transference occurring just before the victim had placed his hand back in his pocket.

Despite this, the absence of DNA is also a challenge, particularly in cases of missing persons in suspicious circumstances.

In the case of long-term missing persons (LTMP) there may be no DNA sample available for comparisons. In these instances it is valuable to obtain DNA from the parents and/or siblings for future proofing identification of the LTMP. On review of case files, should this crucial evidence be absent from files held, it is advantageous to dedicate resources to its collection, particularly with the ever-increasing capability of DNA technology and the hope of identifying human remains.

AVAILABILITY AND SIGNIFICANCE OF WITNESSES

Next to DNA, witnesses increase the capability of solving homicides. It is recognised that witnesses change their story and new witnesses come forward over time to explain things better or, in some instances, recovered memory has assisted in providing crucial evidence to the offence.

It has been suggested that, given a considerable duration of time between the offence and police re-interviewing eyewitnesses, there is a likelihood eyewitnesses will no longer feel threatened from the original occurrence of the crime. In these cases, evidence may be more readily provided to investigators, however care should be given as witnesses may not wish to revisit these traumatic events.

In the event of interviewing witnesses years subsequent to the event, or re-interviewing witnesses after an extended period of time, the investigator must take great care. Extensive literature exists about false memories. Contribution to false memories may occur through:

- Leading questions – to assist in the extraction of information, words utilised can distort the event. An example of such included participants being shown a video depicting a car crash. Afterwards, participants were asked, “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” and alternatively, “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” The use of the first question found respondents overinflated the speed described.

- Non-existent details – or implanting information into a witness’s account, can occur inadvertently through suggestive questioning. This may also occur through the release of information from media appeals at the time, or present calls for assistance, or information on current matters.

- Transformed details – investigators may inadvertently provide information known to them during their investigation of the offence. In releasing this information by seeking confirmation of known facts of the offence a witness may alter their description to align with that of the investigator to seek approval in answering questions correctly, as opposed to simply stating they cannot recall the information sought.

While care must be taken, witnesses generate the highest chance of success in cold case investigation. Often this action leads to new investigative strategies, including the identification of other unknown witnesses and information not previously known.

Frequently, this remains the only investigative opportunity available to investigators. This is prevalent in matters where no physical material or forensic investigation is available, such as persons missing in suspicious circumstances.

Verifying the accounts provided by witnesses and the actions of suspects decades earlier, leads us to the role of intelligence.

INTELLIGENCE, THEN AND NOW

Cold case investigations, by nature, provide unique challenges to intelligence analysts working within this space. Some of these difficulties include:

- sourcing information;

- extracting data from de-commissioned and archaic systems; and

- analysing old and often unreliable data.

While the process for intelligence analysis is much the same for criminal intelligence analysts everywhere, the collection phase — or step two — of the intelligence cycle can be vastly different. The agency currently oversees cases stretching between 1953 and 2016 and analysts are required to adapt their methodology and information sourcing for every case. Mobile phone records, for example, may be relevant for a 2010 case, but were not even in existence prior to the early 1980s.

The age of a case can be both detrimental and advantageous when attempting to source information.

With the explosion of the internet over the last couple of decades, open-source information (OSINT) is readily available and can be of great value to a cold case analyst. Information that was previously difficult or impossible to obtain can now be easily accessed. As time passes, an increasing proportion of historic records, including government archives, are becoming freely available online. Conversely, OSINT can also provide the analyst with current and real-time information such as social media sites in cases where a suspect and/or a witness have been identified yet have not been involved in criminal offending; possibly for decades.

The age of a case, however, often limits the information sources available to the cold case analyst. Telecommunications (telco) and financial records, for example, are only retained by the various telco and financial providers for a limited period, and rarely more than seven years.

Telco records are often used in live homicide investigations extensively and can provide a wealth of intelligence. In the cold case arena, however, this commonly used source of information is often not a feasible option. Even being able to attribute a telephone number to one individual or business at a set date can be problematic, with subscribers changing their numbers periodically. On the rare occasion when early telco records are available, they are often in a different format to current records, making them difficult to analyse.

Financial records can also be problematic, even when records have been retained from the time period of interest. Historically, bank transactions recorded on statements would only be on weekdays, so if a transaction such as an autobank withdrawal was made on the weekend, it would appear on a bank statement under the date of the next working day; usually the Monday. Therefore, the analyst is unable to provide an accurate timeline of events when bank records are relied upon.

Sourcing information from law enforcement agency (LEA) databases can also be challenging.

Government and LEAs, including the WA Police Force, have all undergone system/computer upgrades over the years. As technology continues to develop, new systems are introduced, and old systems are decommissioned. In many instances, the information that is stored in the old systems is not always completely transferred to new systems with some information lost forever. Knowledge and access to the old systems gradually reduces over time, inhibiting data extraction.

In the past, agencies have also purged or destroyed many old records - particularly paper-based ones. There are often inconsistencies in what records were retained or destroyed.

Various government agencies have also been subject to departmental amalgamation and separation. Take, for example, attempting to obtain international travel movements for an individual. The Australian Border Force (ABF) has changed names several times and undergone various amalgamations with other departments since its 1901 inception. Electronic records of historic border movements are only available from 1981, therefore making it impossible to determine if a suspect was even in Australia at the time of the homicide undergoing investigation. Cold case investigators and analysts often face challenges with aspects of the original case file.

The accuracy and the completeness of the information recorded in the case file notes are often not to the standard of today’s case files. An individual’s name, address and vehicles, for example, were not recorded using any standard writing protocols as they are today, and were often incomplete. In one instance, during a recent investigation, the analyst was tasked with identifying and locating a key witness who was only originally identified as Joe Anderson. No full name, date of birth nor address was recorded, and the spelling of the surname was later found to be incorrect.

Another significant issue faced by intelligence analysts working cold cases is the fact that things change with time. People change names and move residences, houses are demolished, and suburbs transformed, businesses move or close and owners change, and vehicles are sold or destroyed. Trying to identify and locate the current whereabouts of a suspect is difficult enough, however if they have changed names over the years (such as through marriage) and moved interstate or overseas, they can be almost impossible to locate with certainty without revealing the existence of an investigation.

SECONDARY VICTIMS

In reaching out to other parties to verify or ascertain data to facilitate an investigation, secondary victims are often consulted. However, poor engagement over extended periods of time with interaction only occurring after significant periods of silence from police, along with a lack of critical support through the years via family liaison officers creates its own challenges.

In these instances, when police do ‘reach out’, investigators hold the potential to contribute to further harm by raising matters that may have been processed and emotionally closed by victims. As such there is a reluctance to relive past traumatic events through another police investigation. Many families may have limited confidence as a consequence of no resolution in previous investigations and will be reluctant to repeat past experiences, potentially reducing their assistance or cooperation with police activities.

Police have a significant impact on the level and influence of grief experienced by secondary victims. Three instances have been identified where police actions impact:

- Lack of communication – with the passing of time, contact from police diminishes, most often based on there being no new information to provide. When this occurs, secondary victims may feel they were not important;

- Victim characteristics – some secondary victims felt police did not commit to the investigation of their loved one’s murder based on the victim being less worthy as they undertook ‘unconventional’ behaviour. This behaviour included drug use, prostitution or perhaps their death resulted from involvement in organised crime activities;

- Self-investigation – some secondary victims believed they knew the identity of the killers and provided information to police, who did not act upon it and arrest the suspected offenders. Clearly, this was due to insufficient evidence to do so, however the impact upon the secondary victim only creates further frustration and criticism of police through their perception of not being heard.

Sadly, resolution and attention to the grief process may only ever occur subsequent to the offender being arrested. In such instances, secondary victims have their chance for justice, learning details of the crime through the court and being able to ‘make sense’ of the murder.

Failing to work with and assist secondary victims can give rise to criticism because of a perceived lack of action by police. In this theatre, publicity may significantly reduce public confidence in police to undertake such investigations. Some comfort may be sought following the request of a reward to renew interest in an unsolved matter.

THE ROLE OF REWARD

The WA Government established monetary rewards for information leading to the resolution of unsolved homicides at the request of the Western Australia Police Commissioner. The value of current rewards was not standardised, and recently underwent a review and restructure.

Previously, not all files held by the squad were linked to a reward. Those which had been, were linked to payout amounts ranging from $5,000 up to $250,000. A significant disparity existed in the rewards offered, with amounts reflective of the value at the time they were issued. Since being issued they have been scaled against earning capacity. For example, the suspicious disappearance of two females in 1974 had a posted reward of $5,000 — which was only recently changed to reflect current standards and expectations of the community.

Recent reward applications submitted to the WA government have received approval, increasing blanket approval for all matters up to a value of $1 million.

While rewards represent an investigative strategy to assist in resolving unsolved cases via arrest, five cases with rewards attached have been resolved in Western Australia through arrest without the requirement of the government to honour payments.

With the assistance of rewards, the squad is undertaking a release of unsolved homicides on Western Australia Police Force social media holdings and Crime Stoppers to generate information, ensuring these matters remain in the consciousness of the community. This also serves to provide support to secondary victims demonstrating that police are not giving up and gives them hope that the offer of a reward encourages individuals to provide information.

CORONIAL INQUEST

In instances where the matter remains unsolved, in a last chance of achieving closure, secondary victims often hold the view that a coronial inquest may help resolve their grief. In some instances, this is seen as the panacea to resolve a file on account of police failing in their original investigation. Secondary victims often view the coronial inquest process as the last chance of identifying what happened to their loved one. This is primarily linked to the view the coroner can compel individuals to answer questions, potentially revealing key new evidence.

While the coroner holds significant powers to undertake an investigation, in Annetts v McCann (1990) 170 CLR 596 at 616 it was determined: ‘… an inquest is a fact-finding exercise and not a method of apportioning guilt. In an inquest it should never be forgotten that there are no parties, there is no indictment, there is no prosecution, there is no defence, there is no trial; simply an attempt to establish facts’.

Where the coroner decides to hold an inquest, the finding or comment must not be framed in such a way as to appear to suggest that any person is guilty of an offence.

CLOSING FILES

Despite the best efforts of investigators, sadly the fact remains that not all homicides will be solved. This is evidenced with unsolved homicide files held across the nation and the globe. The oldest Western Australia file held by the Special Crime Squad – Homicide, is 70 years’ old with the suspicious disappearance of a 17-year-old female from Perth in 1953. On mere speculation, if the unidentified offender in this matter was 18 years of age at the time of the suspected occurrence of homicide, this person would be 88 years of age today.

The likelihood of completing a successful investigation and bringing an offender to court is significantly diminished with every passing year. In the event an offender is identified and arrested, potential arguments are raised as to the public interest in pursuing this matter through the courts.

Regardless, the matter remains with the Special Crime Squad - Homicide with the closure of the file being achieved by completing the investigation to a standard reflective of modern practices.

This ‘unresolved file’ remains in the squad in the hope:

- an offender or an individual:

- provides a death bed confession; or

- leaves a note ‘to be opened on their death’; or

- human remains with physical material are located, permitting an examination to identify an offender or investigative opportunities.

NO HOPE AT ALL

While arrest remains the single goal in every instance, it should not be considered a victory within this field. This is a difficult prospect for any policing agency to accept because this is the most common method to measure success. The resolution of matters is achieved through cyclic inquiries on all files held, which results in the reduction in the number of files, increasing community confidence and – in the case where matters are solved through arrest – justice is finally served.

A single commonality in all these matters is the many grieving families connected to their deceased loved one and their never-ending search for closure. And of course, there is the offender who remains within our community; unpunished for their crime.

The burden carried by surviving loved ones ensures police hold dear a quote by the renowned American author, Dale Carnegie: “Most of the important things in the world have been accomplished by people who have kept on trying when there seemed no hope at all”.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Quentin Flatman APM holds the rank of Commander, Chief of Staff, Office of Commissioner. He has a diverse policing background, undertaking various roles in general policing before becoming a detective. As a detective he worked in the Metropolitan area and State Crime. He led the state’s response to child abuse in Remote Aboriginal Communities in the Kimberley Region. This led to service in Regional Western Australia as a detective and uniform officer at Kununurra, Derby and Albany. On returning to Perth he was the OIC of the Cold Case Homicide Squad, where he led a National Cold Case Homicide Symposium, seeking the creation of national partnerships, and improvements to the management and investigation of historical homicide investigations. He has a Graduate Diploma in Disaster and Emergency Management, a Graduate Certificate in Leadership and Executive Management, and a Bachelor of Criminology.

Allyson Beaton (above) joined the WA Police in July 1988 and after graduating worked as a general duties officer until 1996. She then transferred to the Forensic Division. She undertook study during her tenure within the Forensic Division gaining a Certificate in Photography as well as a Bachelor of Science Forensic Investigation – Crime Scene Examination (Curtin University). In June 2012 Allyson played a key role in coordinating the post-mortem examinations of victims as a result of an asylum seeker vessel capsize off the coast of Christmas Island. Allyson is now currently working at the Special Crime Division where she is managing the response to identify unidentified human remains in WA.

Sally Coombes (above) has over 12 years’ experience in the Intelligence field. She originally joined the WA Police in 2007 as an information officer working at the Licencing Enforcement Division, whilst finishing a degree in Counterterrorism, Security and Intelligence. Sally then moved to State Intelligence in 2011 as an analyst and worked in strategic intelligence. Over the next few years, she spent time in various areas within WA Police gaining experience as an Intelligence Analyst. Then in 2017 she was transferred to the Cold Case Homicide Squad where she worked until being transferred in 2020 to the Homicide Squad. Sally is currently working at Perth District but retains a keen interest in Cold Case files.

Share this article:

Become an APJ subscriber now

Want to read more posts like this one and stay up to date with the latest in Australian policing news? Subscribe to the Australian Police Journal.